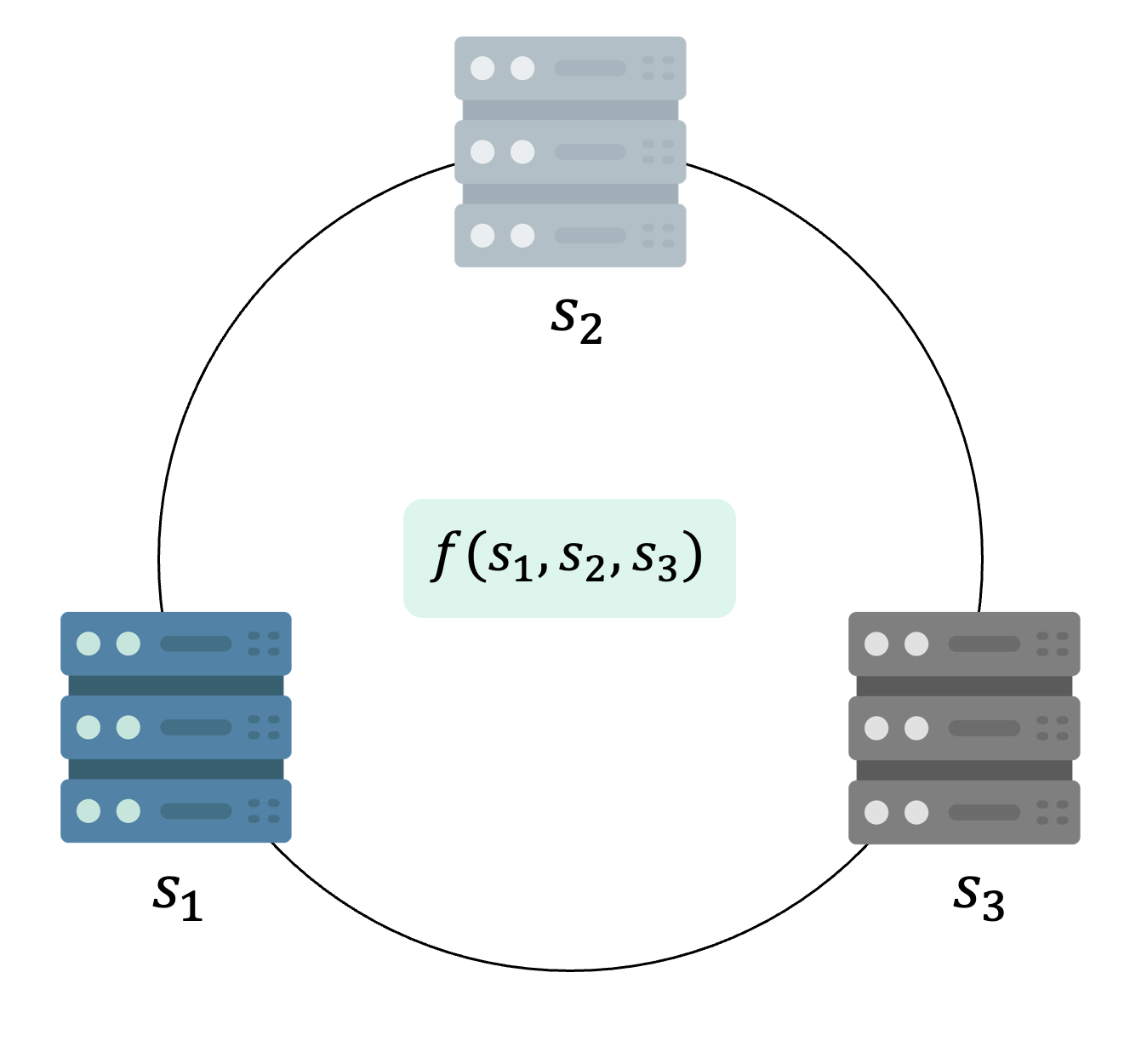

MPC, or secure multi-party computation, is a powerful class of cryptographic primitives that enables a host of privacy-preserving systems. In MPC, $n$ parties each have an input $s_i$, and aim to compute a joint function $f(s_1, …, s_n)$. Because parties can only learn the function’s output, each party’s input is entirely hidden from the rest.

In recent years, milestones in the efficiency of MPC protocols have opened a new door: leveraging MPC in broad-reaching, user-facing applications. But designing and implementing an MPC protocol is only the first step to deploying an end-to-end MPC application.

The authors of this post are working on real-world MPC systems, some that serve many millions of users. In this piece, we bring together our respective experiences to collectively reflect on the following question:

What are the most significant challenges to the development and deployment of MPC applications?

Who are we & how do we MPC?

Signal

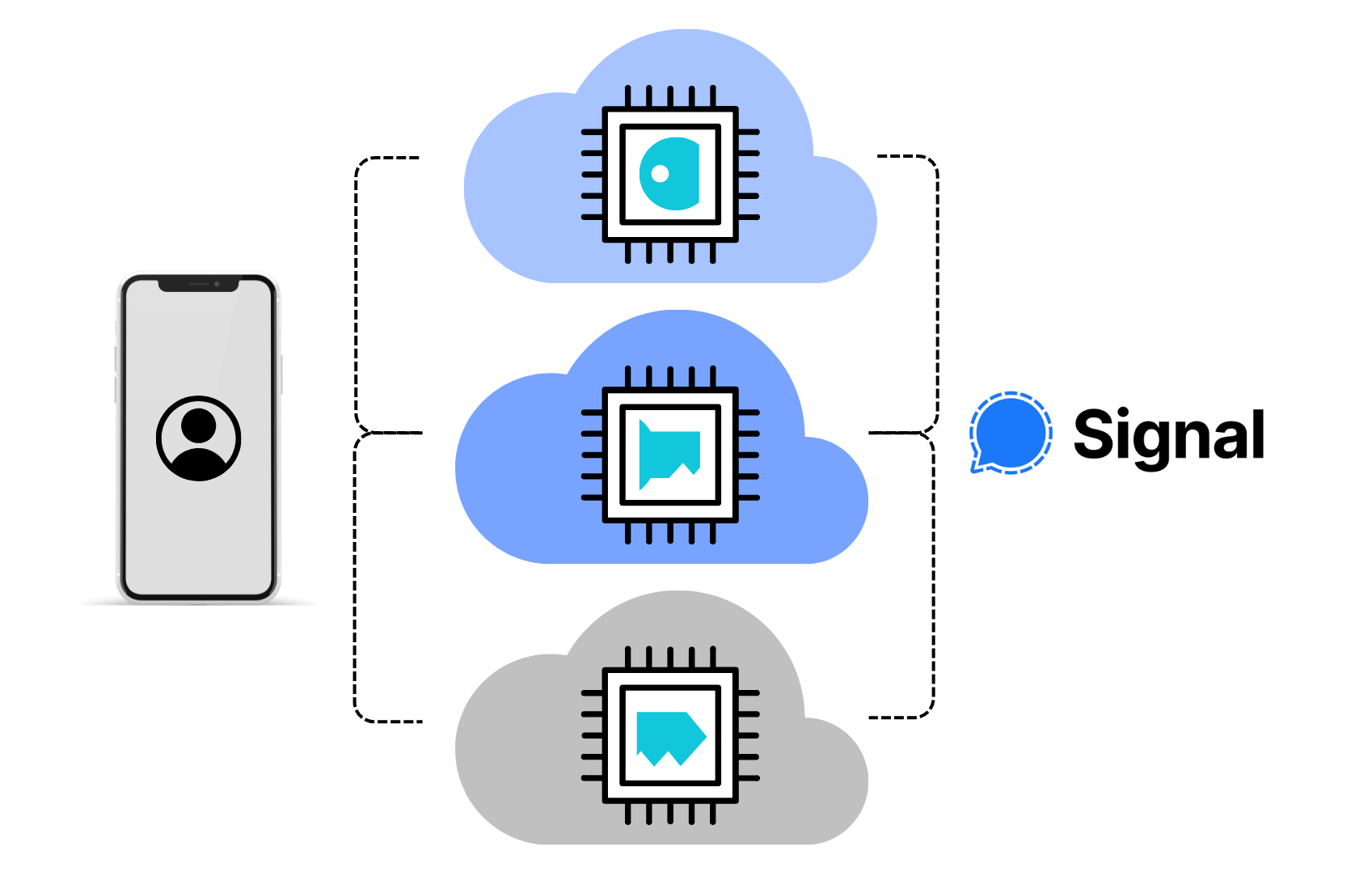

Signal is the most widely used truly private messaging service in the world, enabling private communications for many millions of people across the globe daily. Signal offers a secure value recovery protocol in which users can leverage a PIN to recover backups of account data. The current scheme relies on SGX hardware enclaves hosted on Azure. And, as evidenced in the open-sourced Secure Value Recovery 2 repository, Signal is already making progress toward a subsequent system that leverages MPC, using threshold cryptography and oPRFs. Such a design would allow Signal to distribute computation across multiple hardware platforms offered by distinct cloud providers. This distribution provides significant security benefits: No single server sees users’ passwords or keys and user backups will remain secure even if all but one hardware platform are compromised.

Coinbase

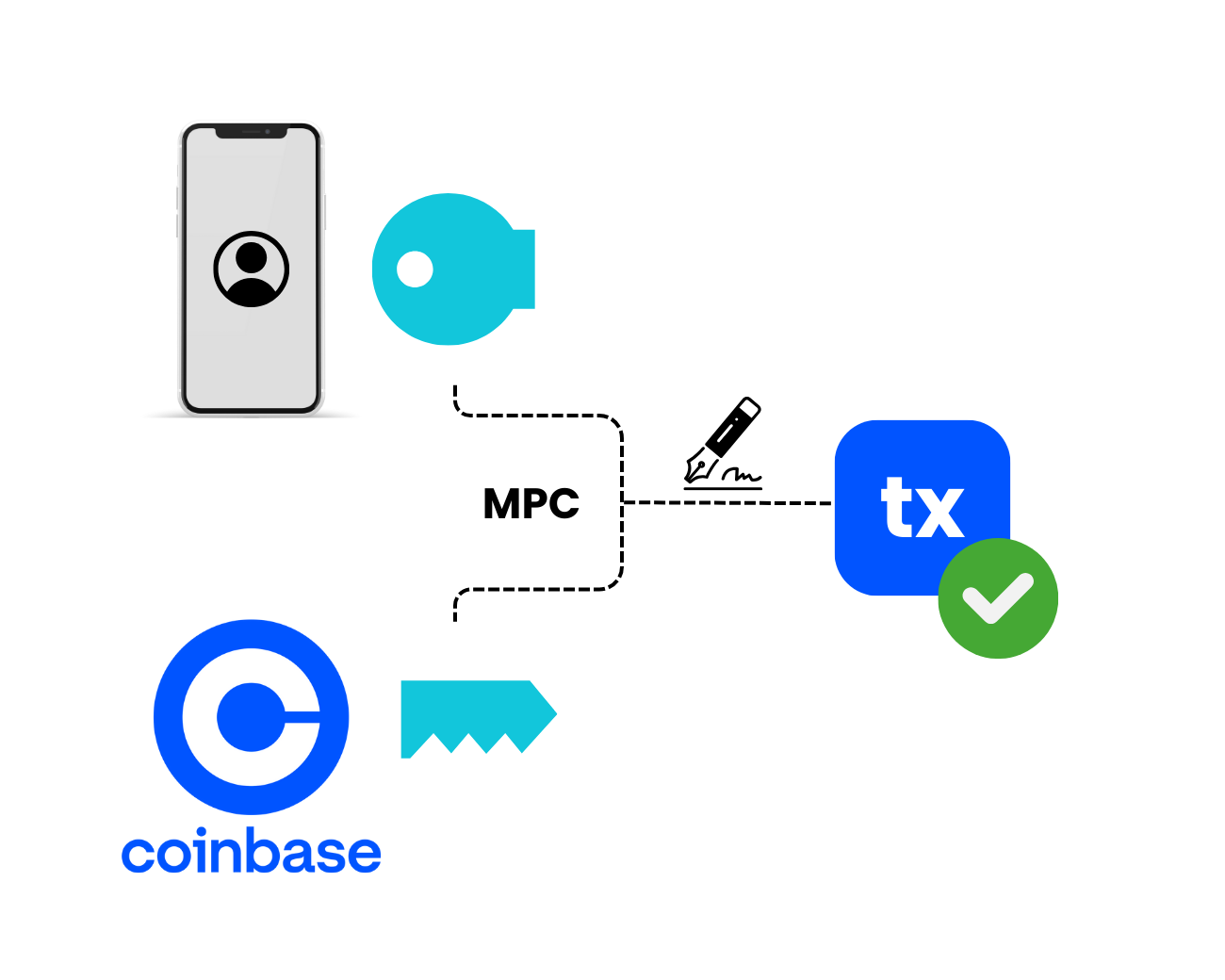

Coinbase is a publicly traded company that operates a leading cryptocurrency exchange platform and offers a broad suite of solutions for institutional and retail customers. Coinbase began to incorporate cutting-edge MPC into its product and security roadmap a few years ago, accelerating this initiative with the acquisition of Unbound Security in 2021.

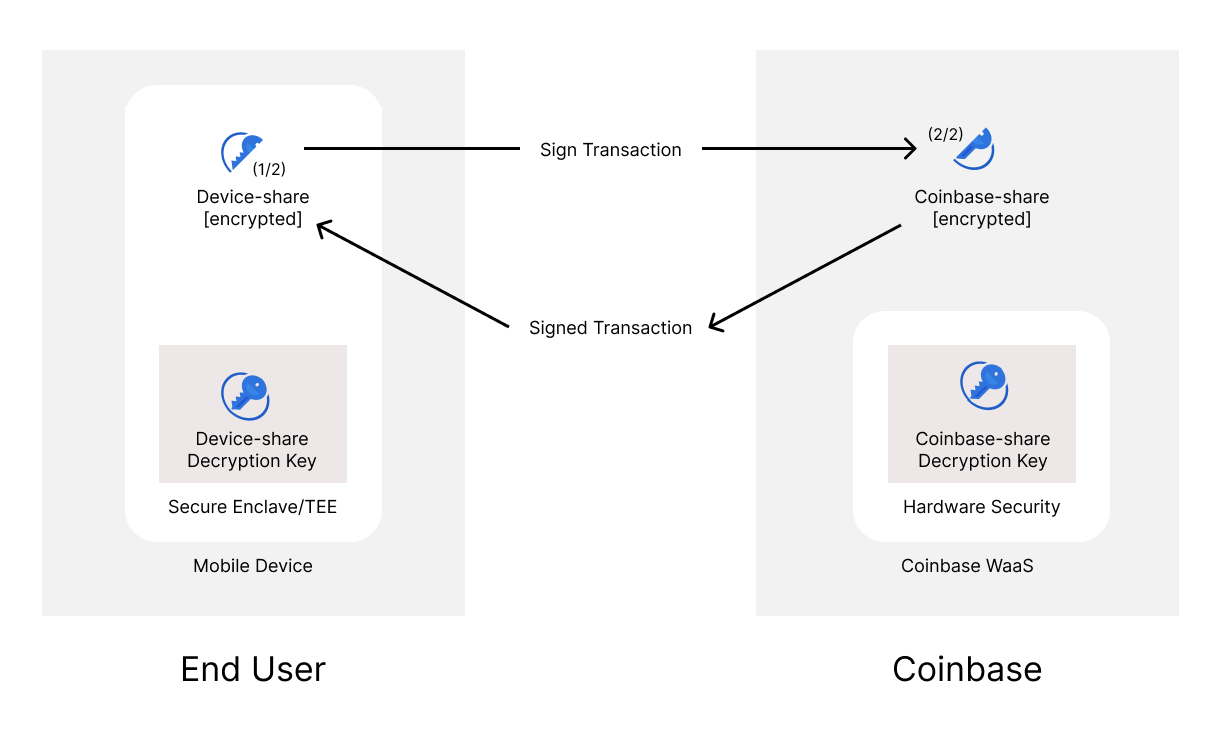

Earlier this year, Coinbase released Wallet as a Service (WaaS), a set of wallet infrastructure APIs that enables companies to create and deploy customizable wallets. WaaS wallets use MPC for generating keys, deriving keys, and generating signatures on transactions. The signing key is secret-shared between the end user and Coinbase. WaaS has publicly-verifiable backups in the case of an end-user losing access to their device. At the user’s discretion, the backup key is either secret-shared between Coinbase and the user, or the user holds both shares encrypted under strong keys. Very recently, Coinbase also released their Prime Web3 wallet, an institutional solution that uses MPC to secret-share keys between the institutional customer and Coinbase.

Internet Security Research Group (ISRG)

ISRG is a 501(c)3 nonprofit that develops public-benefit digital infrastructure projects relating to internet security and privacy, including the Let’s Encrypt Certificate Authority and Prossimo. ISRG also has experience developing and deploying privacy-preserving metrics systems.

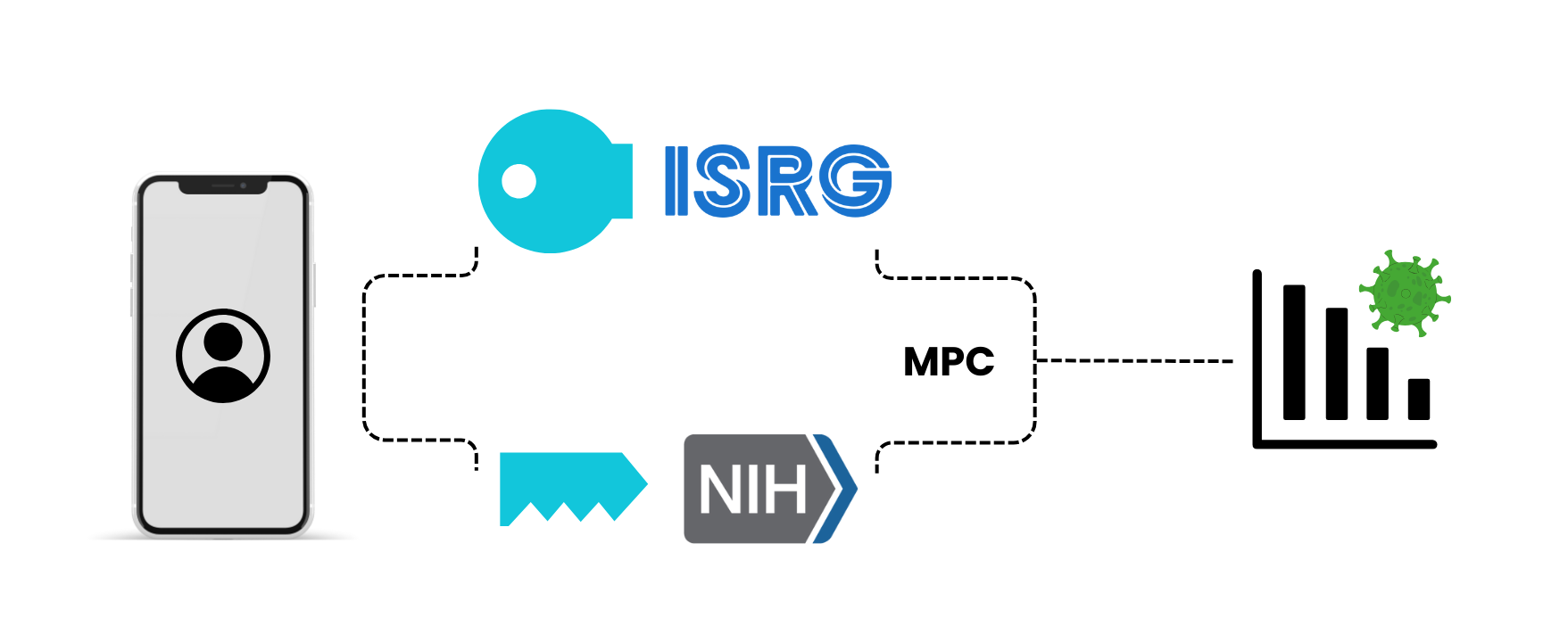

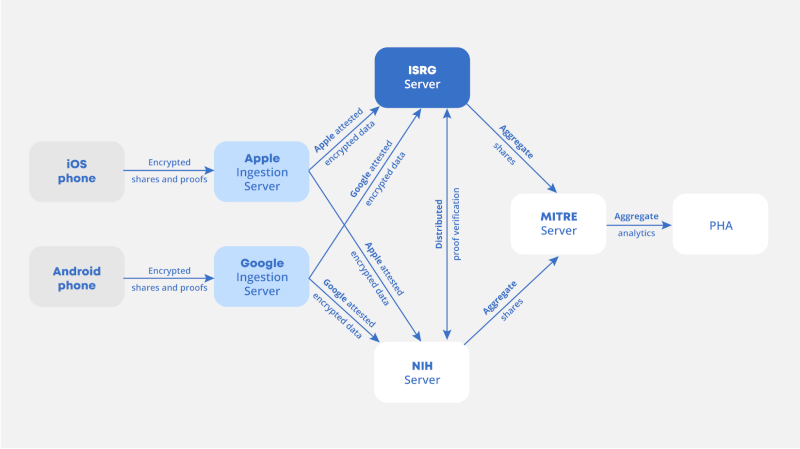

At the height of the COVID-19 pandemic, Apple and Google sought the help of ISRG to collaborate on an exposure notification-related system known as Exposure Notification Privacy-preserving Analytics (ENPA). ISRG, the National Institutes of Health (NIH), and the MITRE Corporation used MPC via the Prio protocol to privately compute analytics over responses from participating Android and Apple mobile devices. As a result, public health authorities could analyze meaningful aggregate statistics about COVID-19 exposures without revealing any one client’s data. ENPA enabled authorities to tune exposure notification thresholds, monitor epidemiological trends, and even estimate the number of COVID-19 infections avoided due to the exposure notification system.

A simplification of ENPA: Clients divide their data among ISRG and NIH, which conduct MPC to yield private analytics.

A simplification of ENPA: Clients divide their data among ISRG and NIH, which conduct MPC to yield private analytics.

Following the success of ENPA, ISRG is now developing Divvi Up, a service built on top of the Distributed Aggregation Protocol (DAP), offering a family of Prio-based variants that support more complex data types. As Divvi Up approaches launch, ISRG is eager to facilitate a broad range of private analytics deployments.

UC Berkeley Security Group

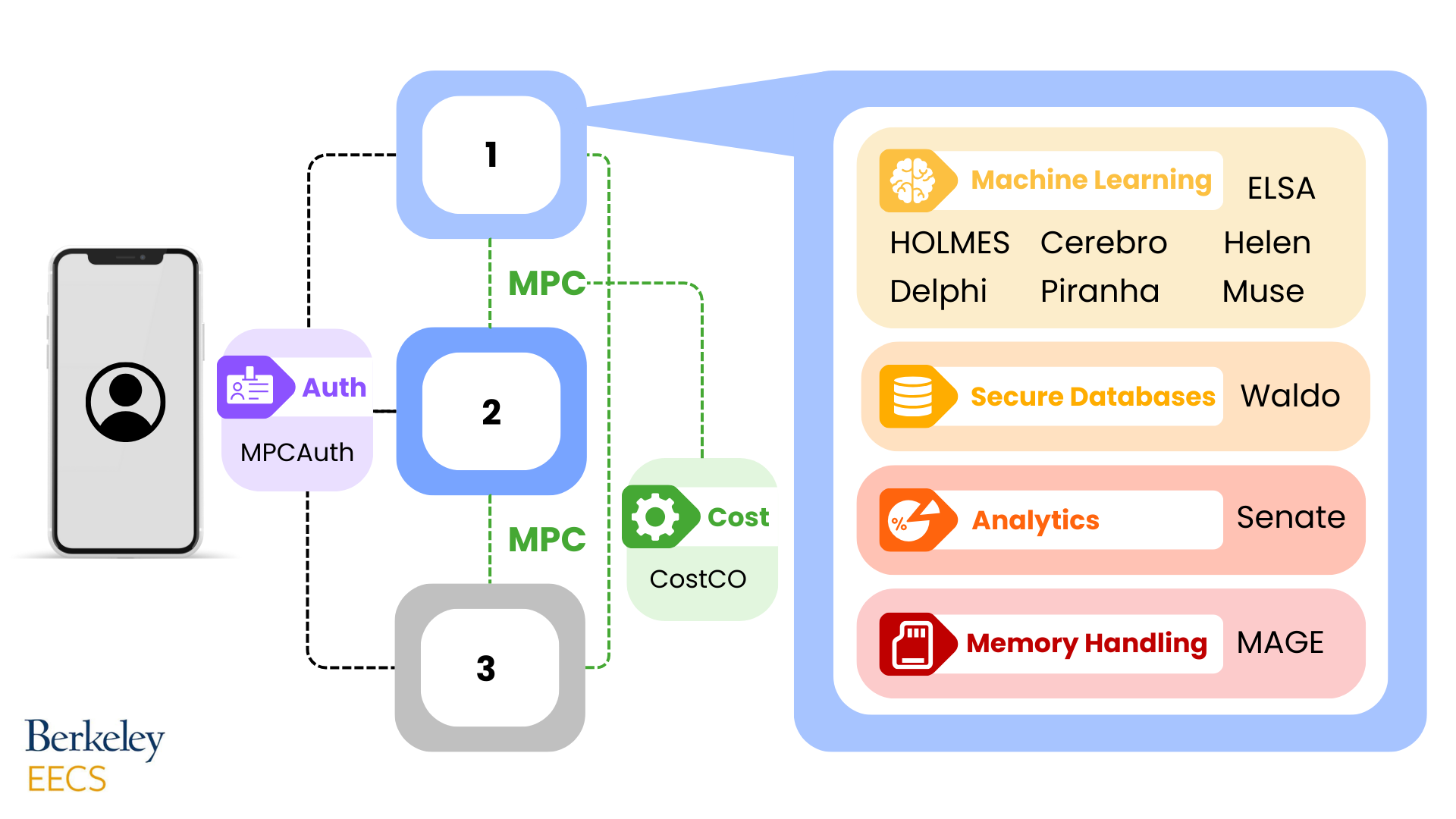

The UC Berkeley Security Group’s research projects in the MPC systems stack

The UC Berkeley Security Group’s research projects in the MPC systems stack

The UC Berkeley security group is conducting research to enable more efficient and easy-to-use MPC systems. This includes MPC systems for collaborative learning (ELSA, Piranha, Helen, HOLMES, Cerebro, Delphi, Muse), collaborative analytics (Senate), secure authentication (MPCAuth), or secure databases (Waldo), as well as rethinking the systems stack for MPC (MAGE, CostCO). The group is hosting a list of MPC deployments at mpc.cs.berkeley.edu based on community contributions.

From pure to practical MPC

In the “Pure MPC” setting, cryptographers assume that MPC parties are run in separate trust domains, establishing strong conjectures and abstractions about their behavior. “Pure MPC” assumes a set of synthetic conditions that cannot be taken for granted in the real world. As we venture beyond the theoretical realm, MPC is no longer run among hypothetical parties with arbitrary degrees of honesty. In a practical deployment, real organizations serve as trust domains, unearthing a host of practical considerations. In fact, deploying MPC in production requires answering a series of questions, such as:

| Who are the parties among which we can run MPC? |

| Who assigns session IDs across multi-round protocols? Are we trusting a centralized entity to assign them? |

| How is key management done? If parties are storing intermediate MPC secret shares, where are they stored? |

| How do the $n$ parties authenticate to one another? |

| How does a client authenticate to the $n$ parties? |

| How do we ensure that MPC parties have secure communication channels between them (such as TLS)? |

| How do we resolve the synchronization challenges that manifest when communicating between parties? |

For instance, many of the bugs that followed ISRG’s initial deployment of the exposure notification system (ENPA) were distributed systems challenges such as scheduling and consensus between the MPC parties, rather than cryptography-specific roadblocks.

In the case of Coinbase, significant effort is invested in writing cryptographic specifications that ensure a secure deployment of a theoretical MPC protocol. There are two types of specifications. The first involves specifying exactly how to implement the pure MPC protocol, assuming that all of the above questions have been answered. The second specifies how participating parties achieve a setting that resolves all of those questions. The typical workflow for the first type of specification is as follows: First, the MPC protocol’s security proof is verified. Once the cryptography undergoes a review process by the security and cryptography teams, a detailed specification is written for software engineers to implement the protocol. Next, the security and cryptography teams confirm that the specification matches the theoretical paper, and that the code matches the specification. The second type of specification relates to how parties set up secure channels, agree on who is participating, what the input is, how secrets are backed up, and so on. As with the first type of specification, these are also reviewed independently by both the cryptography and security teams. After all of this work, the MPC protocol can finally be implemented and deployed.

And so, in many cases, implementing the novel MPC protocol itself ends up being significantly less time-intensive than preparing to deploy the MPC protocol in a practical setting, and a significant amount of work is needed, even given a rigorously proven and reviewed theoretical paper.

Who are these $n$ parties?

Hundreds of academic MPC papers simply state “Assume $n$ independent parties…” This brings us to the most daunting question when it comes to making MPC work in practice: Who are these parties in a real deployment? In a high-stakes security application like Coinbase’s digital asset key management, it is of utmost importance to select parties that maintain sufficient separation between their computing environments. The greater the separation, the more difficult it would be for an attacker to compromise the entire signing key and generate a fraudulent transaction.

Currently, Coinbase’s Wallet as a Service product uses two-party ECDSA signatures, where one party is the user and another is Coinbase. While $n=2$ in this case, Coinbase’s roadmap includes exploring product suites that provide additional flexibility to increase $n$ to more parties for additional separation. Nevertheless, in the wallet scenario when the two sides are in completely different environments (Coinbase’s infrastructure and a user’s mobile or laptop), there is inherent separation that provides a high level of security. This is different from running MPC internally in a single organization, where separation of the entities is critical.

Finally, it is challenging to find a partner that matches the scale of compute and security requirements needed to conduct the MPC in one’s application. In fact, whenever Signal has considered MPC for secure value recovery and other services, a major concern has been finding parties that can simultaneously match Signal’s computing needs and maintain Signal’s rigorous privacy guarantees to its users. Because Signal operates critical infrastructure that needs to be instantly available in order to function, such a partner must also provide infrastructure capable of handling many millions of users, with a high level of fault tolerance, 24/7 support, and the ability to recover quickly upon failure. While Signal uses untrusted third-party service providers today, introducing a business partner, university, or non-profit as a distinct MPC trust domain would implicate trust assumptions. Not only would the third party need to provide a sufficient service level, but users would have to trust the security measures intended to prevent attackers from breaching the separation between the third party and Signal. This would be a significant change since today, Signal goes to great lengths to build its systems such that users do not even need to trust Signal staff. As a result, Signal has opted to approximate these parties through hardware enclaves. Thus, even if MPC parties are hosted by a third party service provider, they have hardware-based guarantees that the memory is protected and that the correct code is being executed.

Determining which parties can function as MPC nodes in real-world contexts often necessitates intensive effort and negotiation, a process that requires balancing complex and potentially competing concerns.

Collaboration is… hard

Partnerships between organizations cooperating to deploy MPC aren’t impossible, but they are rare. In the case of ENPA, while ISRG wrote much of the aggregator codebase, Apple and Google built out their respective client-side applications. However, in ISRG’s experience, collaborating closely with other teams in order to deploy MPC presents a host of its own obstacles, even after the organizations are identified and finalized. For example, since ISRG was providing much of the ENPA software to other parties, ISRG’s engineers had to devote a great deal of resources to simplify the external deployment process for other parties (e.g. making it simple for the National Institutes of Health to deploy onto AWS).

Following the initial deployment, maintenance and testing were the next obstacle. The parties involved in ENPA set up shared infrastructure for testing, including a parallel staging environment. For ISRG, this meant precisely understanding the workflows of other organizations and ensuring they were comfortable with the same deployment software (e.g. Terraform). Testing was particularly challenging; in one instance, all parties involved in the ENPA project synchronously came together to perform a massive cross-organization integration test. In fact, real-time Slack communications were crucial to the maintenance of ENPA. Conducting synchronous communication between teams in order to maintain a complex distributed system is inherently arduous.

ENPA system overview including all involved institutions

ENPA system overview including all involved institutions

ISRG and its collaborators uncovered workarounds to alleviate cross-organizational burdens. For ENPA, there was a significant effort to mitigate such synchronous collaboration. For example, adding a new U.S. State’s clients to ENPA required a significant additional operational workload. As such, ISRG configured the system so that servers could dynamically discover each other’s public keys and mailboxes via manifests at well-known URLs, eliminating the need for all parties to have a call for a configuration file setup. So when distinct organizations are identified, independent setup processes for parties can take the toil out of onboarding new parties. In building the privacy-preserving aggregate statistics service Divvi Up, ISRG has been collaborating with other potential users of the DAP protocol through the IETF Privacy Preserving Measurement Working Group to develop and standardize the protocol. Taking a standards-based approach to MPC enables interoperation with independent implementations, and sets the foundation for an ecosystem around the protocol.

Signal has opted to run MPC parties on hosted hardware enclaves as opposed to third-party partners not only in light of the aforementioned security considerations, but also due to overhead of such a collaboration for a hypothetical third-party partner. Indeed, Signal requires a very high service-level agreement to meet the uptime commitment required by the many millions of people who rely on Signal as core communications infrastructure. In an application utilized on a daily basis by many millions worldwide, Signal must be always available—a property that not all institutional collaborators offer.

Indeed, in Coinbase’s experience, there are two types of institutional users of WaaS-like products: those who are willing to maintain robust infrastructure to serve as an MPC party, and those who simply seek a SaaS-type experience. We cannot expect all entities to fall into the former category.

And oftentimes, even if two collaborating entities are willing to maintain robust infrastructure, this often gets us to $n=2$ MPC parties. How do we get to $n > 2$ for improved security? Is there another solution that avoids involving other organizations altogether?

MPC in the clouds

And so, as with a plethora of modern-day computing, some MPC applications have turned to leveraging distinct corporate cloud infrastructure as independent MPC parties. For MPC deployments, clouds not only offer convenience benefits, but also serve as automatic disjoint organizations. For instance, ISRG made it a point to run the distinct ENPA aggregators in distinct clouds to ensure a compromise of one cloud provider would not impact privacy. After experiencing the convenience upside of cloud computing first-hand, ISRG is kickstarting Divvi Up with cloud deployment.

Likewise, Signal is working on leveraging encrypted hardware offerings from corporate cloud infrastructure as distinct MPC parties, thus ensuring that neither Signal, nor those who use Signal, need to trust these providers, even as Signal can avail itself of the scale, reach, and uptime of these infrastructures. This choice makes Signal the administrator over their cloud deployment. To ensure that those who rely on Signal do not need to trust Signal employees and their administration, Signal publicly shares source code and reproducible build instructions, and uses attestation to confirm that the code published in Signal’s repos is the exact code running on Signal’s servers.

Cloud deployments also implicate system cost. In ISRG’s experience, a core challenge with the cross-cloud MPC setup is that communication can be more slow and costly, with significantly higher latency and egress fees than intra-cloud communication. These frictions led Signal to design an MPC protocol that does not need cross-cloud communication.

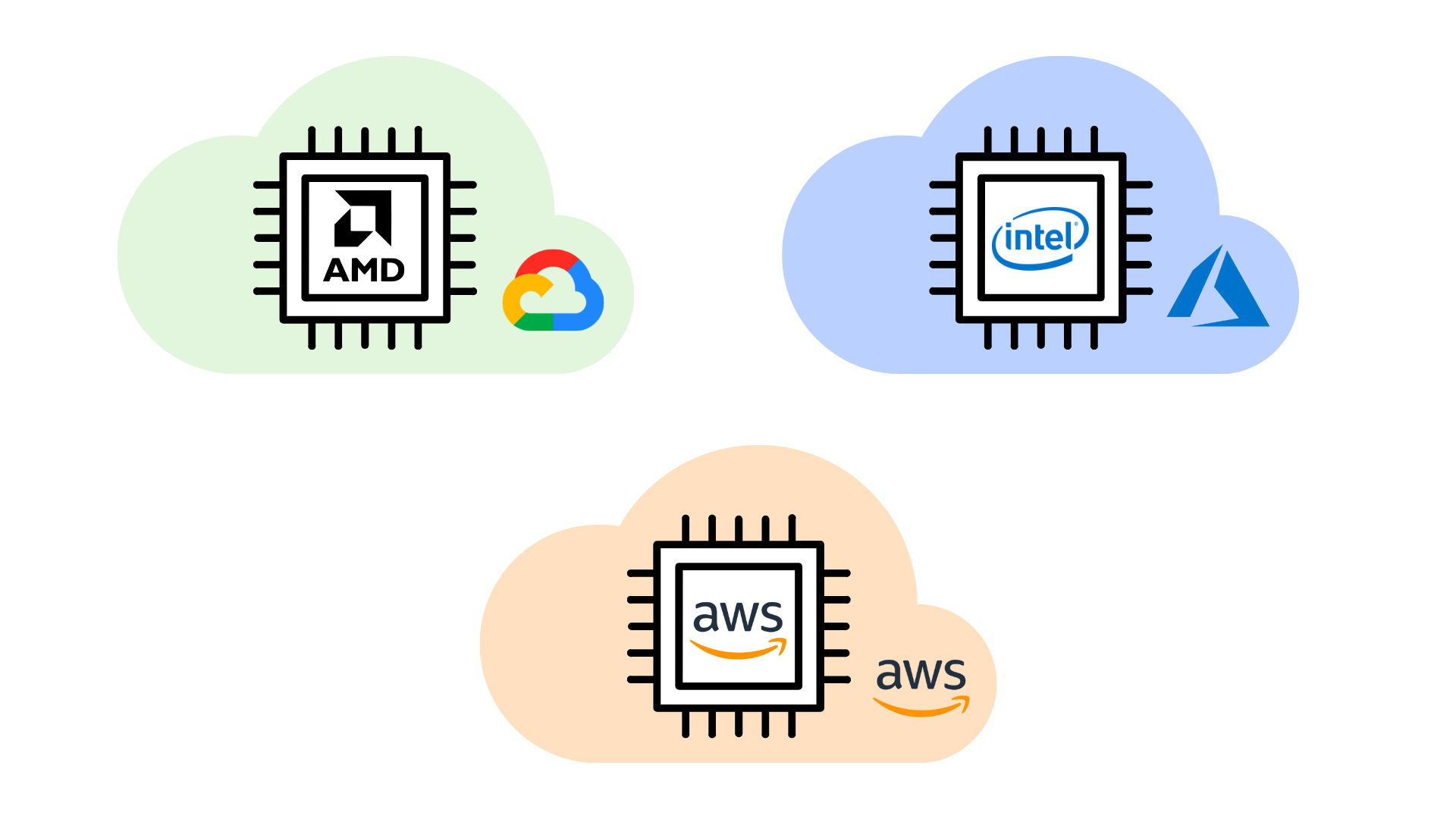

It’s $n$ times the work!

Operating in a multi-cloud setting is challenging, especially when secure enclaves are involved. For example, AWS Nitro involves attesting to an AWS Docker container, while AMD-SEV attests to a kernel, neither of which support application-level attestation like Intel SGX. Recently, Signal allocated significant development resources toward finding ways to achieve acceptable application-level attestation and reproducible builds on multiple platforms, and this remains the foremost obstacle to eventual deployment. Once these issues are addressed, Signal will also need to allocate operations engineering resources towards handling the inconsistencies between the different enclaves offered by distinct clouds. While cross-cloud deployment tools like Terraform exist, they can only abstract away cloud provider differences for the simplest of multi-cloud operations, excluding more complex cloud-specific services such as hardware enclaves.

Cloud providers and their distinct hardware enclave offerings: Google Cloud with AMD-SEV, AWS with AWS Nitro, and Azure with Intel SGX.

Cloud providers and their distinct hardware enclave offerings: Google Cloud with AMD-SEV, AWS with AWS Nitro, and Azure with Intel SGX.

To gain the security benefits of distributing its computation across multiple hardware platforms and cloud providers, not only does Signal need to deploy servers in each cloud, it must also provide distinct attestation for each cloud’s enclave. This means that for every future software update, Signal’s developers must update the codebase for each cloud and each client.

It’s $n$ times the work for $n$ MPC parties! ISRG’s experience with ENPA confirmed this, as it was challenging to write deployment tools that were reused and ported across clouds. The multi-cloud setting is not only $n$ times the work for the application developers, but also for application clients. Indeed, in a cross-cloud MPC application, a client must independently authenticate to each cloud, which can be repetitive, tedious, and time-consuming.

So while cloud computing is a stepping stone to readily available real-world MPC parties, they present serious development and operational challenges.

A perspectival shift on secure enclaves & hardware

Unlike MPC and other advanced cryptography, secure hardware enclaves are incredibly computationally efficient and unrestricted by the circuit implementation of a function.

For some users, hardware enclaves alone may be enough, but they are not a replacement for cryptography. To start, enclaves are known to suffer from side channel attacks. Signal has put significant time and resources into developing novel approaches to mitigate side-channel attacks, including timing and memory access pattern attacks. Moreover, Signal makes enclave-backed services opt-in for users and keeps software and hardware up to date with the latest mitigations. Nevertheless, with hardware-based trust, we can expect attackers with sufficient resources to continue discovering new vulnerabilities, just as we can expect hardware vendors and software developers to continue developing defenses against these new attacks. As such, hardware enclaves serve as an excellent source of defense in depth as components of a larger system, but systems should be designed so that they remain secure even when one or more of the component enclaves are rendered vulnerable. Signal sees enclaves as a supplement to cryptography and a form of defense in-depth, rather than as a sole security measure.

Similarly, Coinbase certainly utilizes cloud hardware security modules for key storage, as well as enclaves on mobile phones to encrypt users’ secret shares. However, it does not rely on enclaves alone. A general consensus among MPC deployers is that enclaves are an excellent secondary security measure when combined with MPC.

It is evident that translating theoretical MPC to practical systems is not easy, and deploying the different trust domains is a core challenge. While cloud computing holds promise to help set up these trust domains in practice, there are significant challenges that need to be addressed before this becomes a robust solution. MPC is a powerful cryptographic primitive that can enable a host of exciting applications and is on the precipice of being embedded ubiquitously in large-scale systems. The key to achieving this reality is cost-efficient, developer-friendly, secure software for deploying MPC.

Learn More

Coinbase: Prime Web3 Wallet Whitepaper , WaaS Whitepaper

ISRG: ENPA Whitepaper, Divvi Up

Signal: SecureValueRecovery2

UC Berkeley Security Group: MPC Deployments Dashboard

* Authors are listed in alphabetical order based on their institutions.